The Peak District was our first National Park and is still one of the most beautiful and most visited in Europe – but we must not forget how the right to access this land was won, nor ever take it for granted.

In this fascinating article, David Toft, Chair of the Hayfield Kinder Trespass Group, tells us all about the Kinder Mass Trespass in 1932, when 600 ordinary men and women took to the moorland of Kinder Scout to protest about restrictions on walking in the countryside. This hugely significant event in the history of the Peak District eventually led to the creation of all the National Parks we still enjoy today.

The Kinder Mass Trespass

Kinder Scout: A Symbolic and Physical Battleground

The Peak District National Park opened in 1951 and was the first of its kind in the UK. It is centred on the Kinder Scout massif, that beautiful, dark, brooding plateau of rugged moorland lying between the great industrial conurbations of Greater Manchester to the West and Sheffield to the East.

It is through this proximity to large populations of politically-aware factory workers that access to Kinder Scout became the symbolic and physical battleground of the struggle between feudal landed gentry and increasingly militant workers, from the late 19th century onwards.

So it was no coincidence that the Peak District was chosen to be the first National Park and it has since become and remains one of the busiest in Europe, with 10 million visits every year.

The park is incredibly well managed by the National Trust, which has large landholdings, the Peak District National Park Authority and the Ranger Service, who together are somehow able to balance the sometimes conflicting needs and demands of farmers, locals, hikers, mountain bikers, campers and car park tourists who flock there every weekend.

The Right to Roam

We take our right to visit this wonderful area for granted, of course, but we shouldn’t. The recent restrictions on visiting areas of natural beauty like the Peak District have reminded us how essential they are to our general wellbeing.

We need to remember that within living memory, access to these hills and valleys and open moors was completely prohibited for ordinary people and that it took a long, hard campaign by people on both sides of the Pennines before the right to walk in this countryside was recognised and respected.

Three of the most important milestones in the long struggle to secure our right to roam took place in the village of Hayfield, and all of them reflected the village’s long relationship with walkers from Manchester, Salford and Stockport.

The first took place in 1876 with the formation of the ‘Hayfield and Kinder Scout Ancient Footpaths Association’, one of the first ever such associations and the result of growing concerns about footpath closures.

Then, in 1894, a meeting took place in Hayfield which revived and expanded this society into what has now become the Peak and Northern Footpaths Society. The meeting in 1894 was led by Manchester radical Richard Pankhurst, husband to Emmeline and one of the founders of the Independent Labour Party.

Over the next three years they raised the money to fight the proposed closure of the ancient Snake Path right of way and scored the most significant victory to that date of preventing closures. A plaque from 1897 now marks the start of the Snake Path in Hayfield and significantly, there is also a plaque at the same spot that commemorates the third and most dramatic of the events – the 1932 Hayfield Kinder Mass Trespass.

“The most successful direct action in British history”

The very idea of trespass, and the implied concept of ownership, goes to the heart of all the struggle for access to our countryside, and there is still much we can learn from the 1932 action – not least because it was spectacularly effective. On the 75th anniversary Roy (Lord) Hattersley described it as ‘the most successful direct action in British history’.

The mass trespass itself was only one incident in a long campaign to gain access to moorland that had once been open to all until the enclosures, something poignantly expressed in this anonymous verse from the 17th Century:

‘The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

But lets the greater felon loose

Who steals the common from off the goose’

Following the end of the First World War, a new generation of young factory workers made use of greater leisure time and cheap rail fares to travel out to places like Edale, Hayfield and Hathersage.

Hayfield was a favourite for walkers from Manchester and Salford and in the 1920s and 30s there was an average of 5,000 visitors each weekend. On Easter Weekend 1930, the railway company counted 14,000 day trippers on the Saturday and Sunday, so it is no surprise that this was the village where impatient young campaigners chose to mount their mass trespass.

Individuals had long trespassed on the moors, often walking long distances from Stockport and the outskirts of Manchester just to get to the hills, where they played cat and mouse with the game keepers, sometimes sleeping out on the moors and facing constant harassment, and on occasions violence. Lengthy negotiations had been taking place between the walking groups and the landowners, but many were becoming impatient with this process.

Marching into the History Books

Members of the British Workers’ Sports Federation in Manchester became increasingly frustrated and decided to force the issue. Following an incident in which he and his friends were humiliated by some gamekeepers near Little Hayfield, Benny Rothman from Cheetham Hill organised the event. A young Jimmy Miller, who later changed his name to Ewan McColl, claimed to have acted as the self-proclaimed press officer, ensuring full coverage in the Manchester Evening News and Manchester Guardian.

Most of those who took part in the Trespass were young – mostly 18 or 19, with Benny only in his early 20s – although most would have left school at 14 and been working in the factories and mills of Manchester since.

Leaflets proclaiming the trespass were widely distributed across Greater Manchester and letters written to The Manchester Guardian and Manchester Evening News, causing great controversy and what we’d now call a twitter storm. The establishment panicked, and on 24 April 1932 all police leave in Derbyshire was cancelled.

On the day, Rothman cycled to the rallying point in Hayfield, partly because he couldn’t afford the train fare and also because he was concerned that the police might try to prevent supporters from joining the protest.

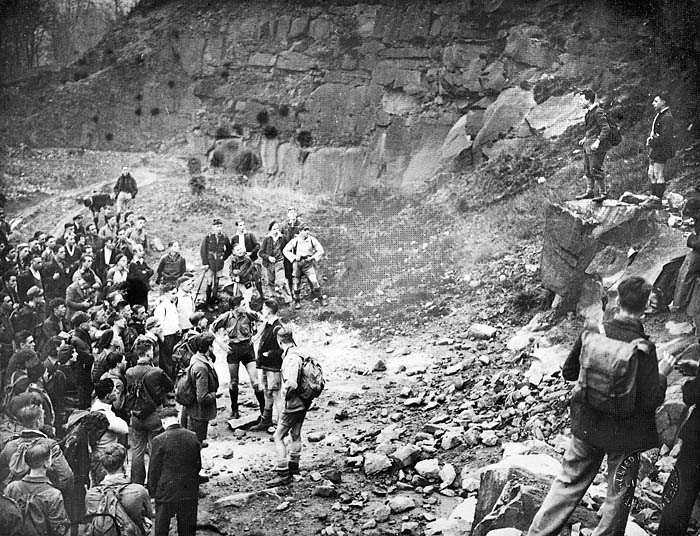

Despite the efforts of the Derbyshire constabulary, up to 600 men and women did make it to Hayfield, with a smaller Sheffield contingent arriving from Edale on the far side of the plateau and others from the Ashop Head end of William Clough.

Everyone, including Benny, were astonished at how many had turned up and avoided police posted on approach stations. The police tactics were what would today be called ‘kettling’ the trespassers, to prevent them gaining access to the Kinder approach routes. Then, according to an unpublished interview with Benny Rothman, the walkers broke through and streamed across Hayfield cricket pitch and onto Kinder Road, ‘singing the Red Flag and the Internationale’.

They regrouped in a quarry at the foot of Kinder, now the Bowden Bridge car park, where Rothman and others addressed them and outlined their strategy for gaining access to the top of the plateau.

They then marched past the reservoir, onto the slopes of Kinder and into the history books.

Arrests and Trials

There were some minor scuffles with hired ‘gamekeepers’, but most of the hikers reached the top and briefly met with their Sheffield comrades, before heading back into Hayfield. There, the waiting police made five arrests, in addition to one for a scuffle with a gamekeeper. Benny Rothman said that all five arrested in Hayfield were ‘Jewish or Jewish looking people’, and he certainly believed that this was deliberately racist behaviour by the police.

The trial of the six took place some weeks later, with full national coverage. There was widespread outrage in liberal and left circles when five of the accused were found guilty by a jury of retired colonels and local landowners.

They were given sentences of up to 6 months hard labour, and it was this, more than anything else, that led to the event becoming such a rallying point at the time and ever since.

Behind the scenes, of course, there was a great deal of low profile, day-to-day hard work in lobbying and negotiating, led by the tirelessly committed Tom Stephenson, who founded the Ramblers’ Association a couple of years after the Kinder Mass Trespass.

He and many ramblers groups initially opposed the trespass and resented what they saw as attention-seeking behaviour that might threaten the painstaking and precarious progress being made.

Tom later recanted, however, and accepted that without the mass trespass, progress towards access would have stalled and the setting up of the national parks would not have happened. Even at the time, he was canny enough to use the event to put pressure on the landowners and politicians by raising the spectre of further mass trespasses should more tangible progress fail to be made.

A Continuing Struggle

The Countryside Rights of Way Act (2000) has consolidated gains in access and helped extend it, and we in the Peak District can consider ourselves very lucky indeed that we have such access as we now enjoy. But we can never afford to be complacent, as a reply from Natural England to an enquiry I made shows:

‘Thank you for your enquiry. The Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 gave the public access to 865,000 hectares of land in England, which is 7% of the total.’

We still have a long way to go – and even existing rights of way still sometimes come under threat. The Kinder Mass Trespass was a crucial event that must not be forgotten, but neither should it be remembered as simply an isolated historical event. Rather, we should celebrate it as an inspirational moment in a continuing struggle that we cannot afford to lose, and from which we can still learn so much.

The Hayfield Kinder Trespass Group

The Hayfield Kinder Trespass Group was founded in 2011. During that time it has worked with many other groups to ensure that the Kinder Mass Trespass and its political lessons are remembered, celebrated and valued.

Its aims include:

- raising awareness of the Trespass and its significance;

- sustaining a high physical profile in the village of Hayfield where the Trespassers congregated;

- taking an active part in village organisations, events and campaigns;

- securing permanent exhibition space to remember and learn from the Trespass;

- sustaining and developing walks and talks with a Trespass theme, to spread the message of the Trespass and to encourage wide diversity of participation;

- identifying opportunities to partner with other groups, agencies, organisations and events to highlight the Trespass; and

- working with educational institutions and professional associations to develop information and teaching events/materials for the same end.

The group can be contacted via their website: www.kindertrespass.org.uk

Climbing Kinder (for the 1932 Mass Trespass)

To these slopes

Here on the sides of this great and ancient plateau’s edge,

Where the curlew sings on a summer’s day

Its solitary, swooping note

Like a crystal drop of Kinder water –

A song far sweeter

Than any music humans ever made –

The walkers came

To claim for all who’d follow

The right to hear that song

To breathe that air with smog-bruised lungs

To taste the sweetness of the open space

To pause a moment from the draining race

Of hard industrial existence

And they called those walkers ‘trespassers’

As if by claiming back these stolen treasures

By repossessing all these hard won pleasures

It was they who were the criminals.

But when you climb up Kinder now

And feel your legs strain hard against the earth

And fill your lungs with fresh free air

And watch the long white hare

Kicking its legs in the very ecstasy of life

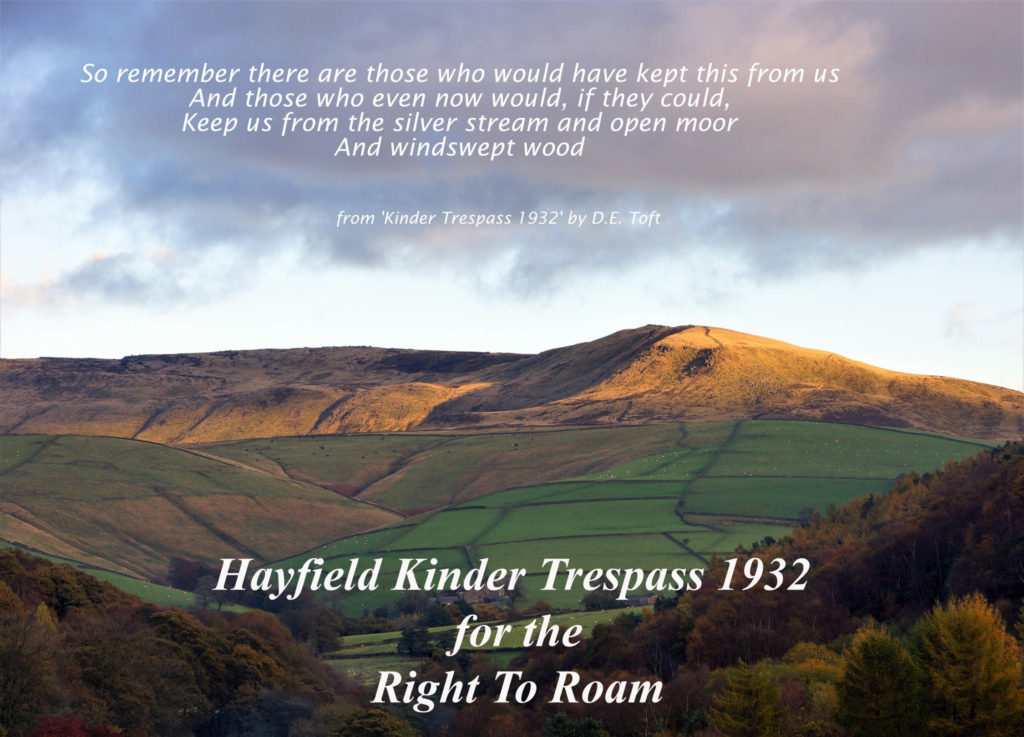

Remember there are those who would have kept this from us

And those who even now would, if they could

Keep us from the silver stream and open moor

And windswept wood.

David Toft

(c) Black and white photographs by courtesy of Keith Warrender and Willow Press

(c) Colour photographs reproduced by kind permission of D E Toft